Options Online Newsletter, May 2006

Win an Options Coffee Mug!

The first three people to correctly answer our question based on the articles below will be sent a new Option Inc. coffee mug. Submit your answer to: kmacaulay@oiweb.com

1. Which of the following could be ergonomic related?

a) Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

b) Headaches

c) Tendonitis

d) All of the above

Congratulations to:

Janice, Dimplex North America Ltd.

Anne, CAW

Neville, Nutech Engineering Inc.

Thank you to everyone who responded!

|

Ergonomics and the Aging Workforce

Companies that have taken a proactive ergonomics approach to reducing musculoskeletal disorder risk factors are well on their way to having safe and productive workplaces for the working population. However, the questions “What about the aging worker?” and “Do aging workers have special needs and limitations, and if so, what can be done to accommodate them?” are becoming more common as employers begin to see and feel the changing workforce demographic.

These questions are explored and answered in the following subject review.

A Demographic Shift Has Begun

With the “baby boom” generation now past middle age and facing longer life expectancy, combined with a lower birth rate, the demographic make-up of our population has begun a period of considerable change that will have a large impact on the near future. This group of employee’s (born between 1946–1964) will raise our country’s average working age to 41 by the year 2008, up from 35 in 1980. Statistics Canada estimates that the percentage of the population between ages 45 - 64 will increase from 29% in 1991, to an estimated 41% in 2011.

The bottom line is that a significant shift in population demographics will occur in the next decade. This will impact on the workforce in two ways. One, with baby boomers making up a large proportion of the workforce there won't be enough younger workers to replace them if they choose to retire. With the possibility of a shortage of skilled management and labour, employers will want to keep their older, experienced workers. This could force a radical rethinking of recruitment, retention, flexible work schedules and retirement. Secondly, a large number of older workers will choose, either because of necessity or for fulfillment, to remain in the labour market. The number of older people who work part-time after ‘retirement’ is already increasing through extended or multiple careers.

Regardless of why older workers remain in the workforce, it is important, to look at their specific needs and to consider what limitations they may have as a natural result of aging. By taking these limitations into consideration, the workplace can then be designed to permit aging workers to function as safely and productively as their younger counterparts.

Limitations of the Aging Worker

As we age, natural changes occur that impact on our ability to work and function in certain manners. Understanding what these changes are is the key to being able to accommodate for them.

Age-related changes can typically be grouped into three main areas: sensory loss, physical limitations and cognitive decrement. Although the actual amounts and timing of age-related changes are highly variable between individuals, general trends have been documented.

Sensory Loss

Our vision deteriorates with age. This includes static acuity (the ability to focus), dynamic visual acuity (the ability to resolve moving targets), contrast sensitivity, decrease in darkness adaptation and colour sensitivity, and greater problems with glare.

Hearing loss is thought to begin at about age 35, but becomes more pronounced with advancing age. It begins in the high frequency ranges and can gradually move to the lower frequencies with age. Most often, this change is noticed as the inability to hear a particular voice or sound in a noisy environment.

Physical Limitations

The impact of aging on the musculoskeletal system of the body can have a large impact in the workplace. It is estimated that strength decreases by about 25% by the age of 65 years. Joint mobility or range of motion is also decreased slightly. In addition, the incidence of arthritis increases markedly beyond age 45, leading the older population to considerable decrease in average joint mobility and grip strength.

Aging workers also face slowing of motor performance and a limitation in the regulation of posture and balance. Older workers have the highest level of fatalities due to falls than any other group. This may be due to the loss of control of postural stability, or a loss of ability to recover balance.

There is also an age-related decrease in cardio-respiratory function. An energy expenditure level at perhaps 80% of the fatigue threshold for a 45-year man, could equate to close to 100% in the average 65-year old worker. Although few occupations demand a high level of energy expenditure such that the NIOSH limits are surpassed for a young employee, they may be closer to approaching the limits for a 65 year old employee.

Older workers who have been exposed to posture and force risk factors over a lifetime of working are at a higher risk of having work-related musculoskeletal conditions, due to cumulative exposure. This underscores the importance of having good ergonomic design throughout a person’s working life, so that they can continue to work at an older age, free of work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

Cognitive Decrement

The cognitive decrement that occurs with age deals with the way people process information. Generally, response time slows, decisions are made more slowly (even more-so if time pressure is present), there is increased difficulty in managing multiple tasks, and increased difficulty working with complex or confusing stimuli is experienced.

The Big Question: Do these age-related changes make the older worker less viable in the workplace?

The answer is NO. With the older worker in mind, the workplace can be modified to account for the limitations of the aging workforce and to take advantage of the benefits of older workers. These benefits are often overlooked but include valuable qualities such as positive work values, less absenteeism, and overall increased reliability. It should also be noted that aging workers tend to have fewer injuries, but their injuries are more severe and they require longer recovering from them.

Designing for the Aging Worker

It has been noted that good ergonomic design is essential to minimizing the risk of problems in the aging years as older workers extend their careers or start new part-time opportunities. While good ergonomic design benefits workers of all ages, it has a direct bearing on the eventual capacity of the older worker. Thus, considering the following recommendations to overcome the age-related limitations of older workers will benefit all workers.

Sensory Design Considerations:

When working on or with a computer screen or any type of electronic display, it is important to ensure adequate illumination, contrast, colours, and font sizes are utilized. Proper placement of visual targets (line of sight) should also be ensured and the amount of ‘clutter’ on a screen be minimized. Consideration of bifocals should also be incorporated into all designs and layouts.

It is important to incorporate adequate illumination, contrast and colour into all aspects of the workplace. For example, painting the treads, risers and landings on stairs different colours will provide additional feedback to a worker ascending/descending the stairs.

Background noise should be minimized and general demands on the auditory system of older workers should be reduced.

Physical Design Considerations:

It is important that the older worker is able to utilize proper working postures and only be required to exert acceptable forces within their essential tasks.

Posture

All movements that are performed on a regular basis should be well within the range of motion for the impacted joints. Postures such as twisting, reaching above the head, kneeling, squatting or static standing for prolonged periods should be avoided. In the case of jobs requiring standing, the implementation of sit/stand stools should be considered.

The possibility of falls should be reduced by decreasing/eliminating the need for overhead reaching which may lead to a loss of balance, using skid-resistant material on floors, and eliminating the use of ladders where possible.

Force

Forces could be reduced through the implementation of material handling solutions which would reduce/eliminate the need to lift, lower, push, pull or carry heavy materials. Hand gripping could also be reduced through the use of jigs or clamps to hold parts instead of hands. Handles should be designed such that workers are able to exert maximum torque with minimal effort. Gripping should also be made easier by utilizing serrated knobs, or using levers instead of knobs for door handles.

Repetition/Duration

Repetitive and cyclical tasks could be reduced by providing workers with a larger and more varied number of essential tasks to perform. Other alternatives include automating processes and modifying job tasks that required prolonged muscle contractions or sustained postures.

Other Factors

Energy requirements for older workers should be reviewed to ensure they are acceptable for an 8 hour day. In addition, consideration should be made for hot conditions or longer shifts. Physically demanding work or working in hot environments may need to be performed at a lower rate, and rest breaks may be essential.

Cognitive Design Considerations:

Some recommendations that could be considered include allowing for a longer response time, providing additional practice (learning time) to increase familiarity, providing frequent refresher training, and reducing the need for simultaneous performance of multiple tasks. Incorporating the allowance for longer response time should be beneficial as it has been shown that aging workers may work slower or make decisions less quickly, but their work tends to be more accurate and decisions more correct.

In addition, the design of the controls and displays should be considered to be user friendly and include maximum usability. For example: Shading area on scale that dials should be turned to instead of requiring the worker to precisely read the numbers.

Summary

As the demographic makeup of the country begins a shift towards increasingly older workers, awareness of the age-related limitations of older workers should be integrated into the application of ergonomic principles to ensure safety and productivity in the workplace for all workers.

As with the application of all ergonomic initiatives, working from a proactive level is the most cost effective and worker friendly method. As a result, since all workplaces will eventually be impacted of an aging workforce, if you have not already, we encourage you to integrate the facts presented here into your design plans and workplace modifications.

If you are interested in discussing any of the information provided here in additional detail, or would like assistance in developing a plan to implement some of these design considerations please feel free to contact us at kmacaulay@oiweb.com.

Resources and Further Reading

Occupational Health & Safety Agency for Healthcare in British Columbia “Aging Workforce and Impact on Ergonomics” http://www.ohsah.bc.ca/index.php?section_id=1343& Occupational Health & Safety Agency for Healthcare in British Columbia “Aging Workforce and Impact on Ergonomics” http://www.ohsah.bc.ca/index.php?section_id=1343&

Belwal, U., Haight, J. ASSE 2005 Professional Development Conference “Designing for an Aging Workforce” http://www.asse.org/aging%20popHaight05PDC1105.pdf Belwal, U., Haight, J. ASSE 2005 Professional Development Conference “Designing for an Aging Workforce” http://www.asse.org/aging%20popHaight05PDC1105.pdf

Haight, J. Professional Safety December 2003 “Human Error & the Challenges of an Aging Workforce” http://www.asse.org/Haight%20Feature%20Dec2003.pdf Haight, J. Professional Safety December 2003 “Human Error & the Challenges of an Aging Workforce” http://www.asse.org/Haight%20Feature%20Dec2003.pdf

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety “Aging Workers” http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/psychosocial/aging_workers.html Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety “Aging Workers” http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/psychosocial/aging_workers.html

HRSDC website “Challenges of an Aging Workforce” http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/en/lp/spila/wlb/pdf/overview-aging-workforce-challenges-en.pdf HRSDC website “Challenges of an Aging Workforce” http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/en/lp/spila/wlb/pdf/overview-aging-workforce-challenges-en.pdf

American Associate of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute: “Health & Safety Issues in An Aging Workforce” http://www.aarp.org/research/work/issues/aresearch-import-383-IB49.html American Associate of Retired Persons Public Policy Institute: “Health & Safety Issues in An Aging Workforce” http://www.aarp.org/research/work/issues/aresearch-import-383-IB49.html

Worker’s Compensation Conference 2005, “The Health & Safety of the Aging Workforce” http://www.dli.state.pa.us/landi/cwp/view.asp?A=138&Q=220377 Worker’s Compensation Conference 2005, “The Health & Safety of the Aging Workforce” http://www.dli.state.pa.us/landi/cwp/view.asp?A=138&Q=220377

Is Ergo Matting Fatiguing or Anti-fatiguing?

Many workplaces use matting to protect their workers for many reasons. It may be an anti-skid mat in a kitchen to prevent falling on a slippery floor, it may be an anti-vibration mat placed on a vibrating platform, or it may be an anti-fatigue mat placed on the floor of a manufacturing plant. There are many different types of matting available from safety supply stores.

So, what makes matting ergonomic or anti-fatiguing? And when should it be used?

Matting that is ergonomic or anti-fatiguing has been designed to induce a slight sway in the posture which requires a slight activation of the muscles of the legs and improves blood flow in the legs. This is believed to decrease the overall feeling of fatigue in the muscles and reduces the amount of blood pooling in the legs.

Ergonomic or Anti-Fatigue matting is useful when working on concrete floors especially when static standing is part of the workers duties. Static standing is standing in one location with little change in position and has been associated with increase pain and discomfort in workers (King, 2002) as well as pooling of blood in the legs. Standing in one position may also place increased stress on our joints as they are made to move and not to be locked in one position for prolonged durations.

Many employers and worker tout the reasons for the placement of matting as an overall increase in comfort for the worker. Studies examining discomfort associated with walking and standing on cement vs. matting would support this claim. However, it should be noted that walking on a very soft mat may actually induce fatigue as it would require the leg musculature to work harder. As a result, softer flooring material can result in higher fatigue ratings despite the perception that softer flooring is more beneficial.

What should we be looking for when considering ergonomic or anti-fatigue matting? Or should we be considering it at all? And with so many types of matting which is the right one for your company? So many questions!

Before you install matting plant wide you need to take a step back and do some ground work. A logical starting point would be to look at your problem area and more specifically, the design of the job. Ideally, a job should be designed to require a variety of postures. Designing jobs that require walking, standing, using footrests, and intermittent sitting postures will best decrease the majority of problems associated with static standing and walking on hard surfaces. As a result, if you can change the design of the job to eliminate the concern you will have a better chance of improving workers comfort than by just installing matting.

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to design/re-design jobs in this way. When this is not possible, you should consider the following to assist in choosing the right matting option for your company.

- Assess the Area -What type of environment is the work being done in? Is there oil or any other substance that regularly falls on the ground? Is it a Class 1 booth requiring static dissipating material? Is there a change in elevation in the job? What is under the matting (i.e. grating, cement)? Is vibration a concern?

- Analyse the work/working postures -What type of work is being completed? Is static standing required? Is the worker required to change their foot placement frequently (i.e. twist or shuffle their feet)? Can a foot rest be added?

- Analyze the traffic/movement in the area - How much wear will there be? Is it a high use area? Will carts be transferred over it? Will there be a high need for replacement and will cost be an issue?

Things to remember:

- At this point in time there have not been any definitive studies investigating what degree of compression, cushioning or sway is best to provide benefits or how much is too much. As a result, we must rely on the questions as stated above to guide us in our decisions.

- Anti-slip mats and other regular mats are NOT anti-fatigue mats!

What to look for in Ergo or Anti-fatigue matting:

- Anti-fatigue mats should be designed so that they do not slide on the floor

- Be sure that the outer mats have sloped edges so that they don't become a trip hazard, and it is still easy to roll carts over them without running into a bump.

- Easy cleaning and sanitizing of the mat is important. Workers are less likely to use mats if they are difficult to clean.

- Matting is appropriate for the area – ex. Ensure that it has an antiskid coating if it could become slippery or that it has holes to allow materials to fall through if required.

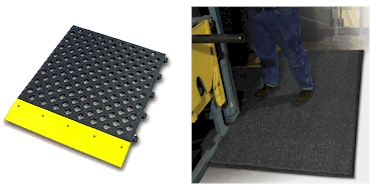

Examples of Matting

Anti fatigue matting can come in a tile form, sheet or roll. The type you choose depends on the answers to the previous questions. For example, if oil or other liquids are a concern and the area is cleaned regularly you may want to invest in a mat with holes to allow the liquid to fall through and is easy to lift and replace to allow for ease of cleaning on a regular basis.

If you are working in a small workstation, tile matting that is easy to put together may be more desirable over placing matting across an entire shop floor.

Matting can have holes, or small bumps on the top or a foam bottom, all of which induce the slight sway to the body. If possible, obtain a small amount of matting to trial under the work conditions and ask for feedback from the workers. Compare two different types of matting for a maximum feedback but remember not everyone will like the same matting. Use your assessment of the area and the points made above to assist you with your decision

Matting Alternatives

Insoles

Insoles with anti-fatigue properties are an alternative that is becoming more widely available from safety supply stores. The advantage to this is that workers can try different levels of cushioning or support thus the end result is customized to their needs. Further, static dissipating insoles are available for use in i.e. paint booths where matting is sometimes an issue. Depending on the size of the area and the number of workers that work within the area, the insoles may be a more cost effective solution. However, how often they need to be replaced will also need to considered in the overall cost.

An example of insole is from Mega Comfort  (http://www.mega-comfort.com) (http://www.mega-comfort.com)

Ergomates

One of the newest forms of anti-fatigue matting is Ergo Matting that can strap on to your safety boots or shoes. These are a sandal type – ergo matting that attaches via straps to the bottom of your shoes. An example presented below is called the Ergomates. Like all matting, however, under extreme conditions (such as walking over metal grating or certain chemical uses) they may breakdown quicker than under normal wear.

An example of insole is from Mega Comfort  (http://www.ergosusa.com/html/ergomates.html) (http://www.ergosusa.com/html/ergomates.html)

General Comments and Suggestions

No matter which direction your company chooses to go with regards to matting, the workers should ensure that they have a good fit with their work shoe/boot. Using shoes that mold to the workers feet and cause a minimum of pressure on all parts of the foot are ideal. Due to swelling that occurs during standing, purchasing shoes one-half to one size larger than you normally would wear is an option. A good time to buy work shoes is right after you have been standing for an extensive length of time. When buying shoes, the worker should ensure that they are able to wiggle their toes. Workers who stand for long hours should buy shoes that have laces at the ball and the top of the foot, to accommodate for swelling and also to make adjustments for two different-sized feet. When buying insoles workers should request insoles that breathe, to minimize moisture and problems such as fungal infections.

References

Rys, M., Konz, S., Standing, 677-687; Ergonomics 37/4, April 1994.

King, P.M., A comparison of the effects of floor mats and shoe in-soles on standing fatigue, 477-484; Applied Ergonomics 33/5, September 2002.

http://www.ohcow.on.ca/resources/handbooks/working_on_your_feet/working_on_your_feet.htm http://www.ohcow.on.ca/resources/handbooks/working_on_your_feet/working_on_your_feet.htm

http://www.stevenspublishing.com/Stevens/OHSPub.nsf/ http://www.stevenspublishing.com/Stevens/OHSPub.nsf/

http://www.ohscanada.com/SafetyPurchasing/Ergfloor.asp http://www.ohscanada.com/SafetyPurchasing/Ergfloor.asp

Are you being as “Proactive” as you can be?

Do you want to maximize the impact of an ergonomic assessment or service? Do you want to minimize your stress levels and help meet external deadlines? By making ergonomic assessments, physical demands analysis, and general ergonomic education programs part of your proactive internal company system, you can accomplish this and more!

Ergonomic initiatives can be beneficial and applicable to multiple domains within a workplace, including: health and safety, human resources, engineering, as well as, general production areas. However, typically, the impact on each of these departments is influenced directly by the timeliness of the ergonomic initiative. As a result, the earlier or more proactive that an ergonomic initiative is launched, the more utility it has. Basically, planning ahead pays off!

The following section looks at the impact proactive ergonomic initiatives can have on various areas within a number of domains.

Health and Safety and Human Resources domain - In the first quarter of 2006, the Ontario Ministry of Labour (MOL) launched a new campaign focussed on Ergonomics, entitled “Pains and Strains” campaign (http://www.labour.gov.on.ca under “Pains and Strains”). This program focuses on awareness, education and prevention of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and brings to the forefront the importance of preventative ergonomics. The importance of awareness, early intervention and proactive ergonomics shouldn’t be a surprise to us. However, the fact that in the near future MOL inspectors will be auditing workplaces for the presence of such programs might be.

In addition to meeting the MOL “Pains and Strains” recommendations, an ongoing requirement within the H&S and HR domain is to meet WSIB needs when filing a Form 7. The need for an accurate “description of the physical activity required” within a job when filing a Form 7 document with WSIB can be dealt with on an as needed basis or proactively. If handled on an as needed basis, this could result someone having to complete a portion of the WSIB PDIF form, for each job in question, quickly to meet the WSIB 72hr deadline. Or if this need was addressed proactively, it would simply require you to submit a previously completed PDA which would save you time and stress.

Proactively meeting the needs and recommendations of the MOL and WSIB may seem like a large project, however, implementing a solid ergonomics program is both feasible and economical if completed in a planned and strategic manner.

The first step would be through auditing your current ergonomics program. This would identify the areas of your program that require additional support to become more proactive. This additional support could include any of the following: implementing training and workshops for specific staff or high risk areas, monthly “Ergo Promo’s” for plant wide awareness, and/or developing a structured program for completing and maintaining a current database of PDA’s.

Engineering domain – The MOL “Pains and Strains” campaign is also relevant to the engineering domain as engineers are able to impact the design of new workstations on a proactive basis, and thus hopefully prevent musculoskeletal injuries.

Integrating ergonomics into the iterative design process is logical and cost effective. The cost of addressing ergonomic concerns on a Reactive basis, instead of Proactive, results in costs to address and treat claims as well as the costs of changing the design at a later date. Data from the MOL website states that MSDs account for 42% of all lost-time claims, 42% of all lost-time claim costs, and 50% of all lost-time days. From 1996 – 2004, there were 382,000 lost-time claims resulting in 27 million lost-time days and direct costs of $3.3 billion. Ontario employers also paid billions of dollars in-direct costs, including lost productivity, re-training, overtime, equipment modifications, and administration. These statistics and costs are valuable when utilized in a cost benefit statement to justify ergonomic changes.

Proactively integrating ergonomics into the engineering design process is both feasible and economical if completed in a planned and strategic manner.

The first step would be through auditing your current engineering design process and identifying at which stage ergonomic input is incorporated. The current stage at which ergonomic input is considered would impact the types of changes that could be considered to maximize early ergonomic intervention. These changes could include any of the following: implementing training for specific engineers, utilizing our Engineering Ergonomic Design Guidelines, and/or arranging for ergonomic assessments of computer based or mocked-up workstations or equipment at key points in the design/implementation phase.

If you are interested in discussing how to move ergonomics upstream at your company – from reactive to proactive – please do not hesitate to contact us, kmacaulay@oiweb.com .

Yoga at your Desk

by Carolyn Weatherson

www.carolynweatherson.com

Taking 5 minutes out to stretch can make a world of difference to your day. These next few exercises focus on the trouble areas associated with desk work; namely posture, tension in the neck and shoulders, the carpal tunnel area and back and abdominal weakness. Focusing on your breath during the practice will relax and rejuvenate your mind. **

Seated Mountain Pose: Begin by coming to the front of your chair and positioning your ankles directly under your knees. Straighten your spine and engage your abdominal muscles. Slide your shoulders back and down and close your eyes. Soften your forehead and your jaw and begin to focus on your breathing to the exclusion of everything else. Remain like this for at least 10 long, slow breaths. Continue to focus on your breath and pull in your abdominal muscles throughout this and the following exercises.

Tension Relieving Stretch: Tilt your right ear toward your right shoulder and tuck your chin in slightly. Stretch the heel of your left hand out and away. Feel the gentle stretch going down your neck, your shoulder and all the way down your arm. If you would like a deeper stretch place your hand on your head allowing the weight of your hand only to increase the stretch. Do not pull your head to the side. Hold for 6 long slow deep breaths. Repeat on the other side.

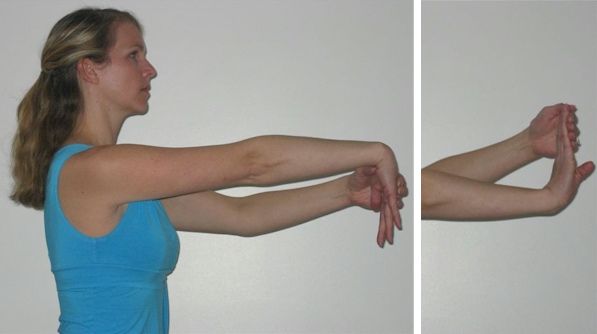

Carpal Tunnel Stretch: Bring your arm up to shoulder height, making a stop sign with your hand. Gently press your fingers back for several breaths then press your hand down for several breaths.

Chair Twist: Begin in seated mountain pose. Take your right hand to the outside of your left knee. Twist to the left and bring your left arm to shoulder height on the back of your chair. If your chair height is not suitable bring your left hand behind your bottom with your fingers pointing away. Each time you inhale, get a little taller. Each time you exhale gently twist a little deeper. Hold for 6 breaths and repeat on the other side.

Seated Side Bend: Inhale your arms up and over your head. Turn your palms forward and clasp under your right wrist with your left hand. Inhale and get long. Exhale and gently bend to the left. Be careful not to tip forward or to pinch your shoulders up. As you become more flexible, you will be able to look up and slightly turn your torso up. Soften your face and hold for several breaths. Repeat on the other side.

Hip stretch: Cross your right foot over your left knee. Bring your hands behind you and open your chest. Inhale and get taller. Exhale and lean forward with a flat back. Each time you inhale, get your spine a little longer. Each time you exhale, get down a little deeper. Continue for several breaths then slowly rise up with a flat back. Repeat on the other side.

If you are interested in setting up a Corporate Yoga Workshop contact Carolyn at 519-824-8369.

** Exercise is not without its risks. To reduce the risk of injury in your case, consult your doctor before beginning this exercise program. The instructor and advice presented are in no way intended as a substitute for medical consultation, the instructor disclaims any liability from and in connection with this program. As with any exercise program, if at any point during the stretches you begin to feel faint, dizzy, or have physical discomfort, you should stop immediately and consult a physician.

|