Archived Articles 2002

Topics of Interest

- Jump start your Committee

- Case Study: Ergonomics in Purchasing

- Online Training - Is it Cost Effective?

- Ergonomics: Cost Savings extends further than injury cost reductions

- Useful Links

- Case Study: Automotive Seat Assembly Company

- Heat Stress

- OSHA Introduces a Plan for Voluntary Guidelines to Reduce Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSD's)

- Working and Lifting Safely During Pregnancy

- The Role of Ergonomics in the Return to Work Process

- What is CCPE?

- Make your "two cents" count!

- Summary of NIOSH Back Belt Studies

- Children and Computers - do they fit together?

- Is prolonged standing a risk to workers? If so, how can we address it?

- Psychosocial Issues - How do they affect the Risk of Musculoskeletal Injuries?

So your committee has been trained on ergonomics. Are they actually using their skills? We have found that often takes one successful case study to give the committee the confidence to implement an ergonomics program. As a result, we are now offering a follow up service that compliments the committee training.

We will attend 3 committee meetings (all within a 6 month period) and guide the committee through a current ergonomics case study. This package includes the following,

To Top

- Ergonomist present at three committee meetings (approximately 3 hours each).

- One hour prep, before or after meeting, to conduct onsite case study evaluation or review.

- Ergonomics support and guidance on how to deal with the concern, what tools to utilize, and assist with brainstorming recommendations.

- Professional support to committee members during case study via telephone or email on an as needed basis.

Case Study: Ergonomics in Purchasing

As individual consumers we are becoming more educated and aware about what a product can offer us. This is also apparent in large corporations where they are looking to purchase smartly, efficiently and economically. The last thing a corporation wants to hear after purchasing new equipment company wide is that the equipment does not accommodate a portion of their working population. This could require the completion of retrofits on brand new equipment, not a desirable or an economical move.

As a result, companies are looking to utilize methods that will assist them in smart procurement. It was under this premise that we were contracted to develop ergonomic based procurement guidelines for office workstations, office chairs, and articulating keyboard trays for a Nation-wide financial/ insurance company.

To provide this support we analyzed the working population at this company to get an understanding of the user population. The results confirmed our initial suspicions that we needed to base our guidelines on the entire potential working population. This required us to utilize the full range of anthropometric data.

With reference to accepted ergonomic standards, guidelines, and work specific tasks, we identified the minimum parameters that each piece of equipment required. Optional or recommended, but not required, features were also identified. We then looked to the anthropometric guidelines to identify the ranges that the equipment must adjust through in order to accommodate the entire working population. For certain pieces of equipment, namely office chairs, this resulted in us suggesting the need for two chairs to meet the adjustability range required. As all other features on the chairs could be adjustable to accommodate the entire population, this would result in one chair being reserved for users in the lower half of the anthropometric range and the other for those in the upper half.

These guidelines were then used to develop the Request for Proposal (RRP) and evaluate the equipment proposals. The potential bidders were narrowed down to two contenders by cost, warranty and other procurement parameters. The final chair was selected based on the number of recommended/optional features provided. As a result, this company has purchased a chair that meets their procurement parameters as well as the requirements of their working population.

* To allow for maximum use and relevance, the ergonomic procurement guidelines have been modified to be applicable to a typical office environment and to the entire working population. These guidelines are available for use in our Members only section. Please contact us for more information on how to become an OIWEB Member.

To Top

Online Training - Is it Cost Effective?

With the current level of technology, the fast pace of the workplace and our demand for a good return on our investment, Online training just makes sense. Online training is quickly being embraced as an effective and economical method of training.

Training our employees, whether it is to work more safely, to learn new work methods and techniques, or to tune their management/leadership skills is recognized as a good investment. Traditionally this has required either a trainer to be brought onsite, or employees to be sent to a training location. Regardless, this has required a significant amount of downtime. In attempt to minimize downtime and maximize efficiency, while utilizing available technology, the development of Online training has occurred.

Significant research has been conducted to evaluate the effects of online training. This has focused around cost effectiveness: primarily looking at reducing costs, improving learning, and increasing volume.

When we think about Online learning our first impression may be that it would be costly to implement, and end up costing the same if not more than traditional training. In fact, research suggests the opposite. Online training can save costs by surprisingly reducing the time it takes to learn.

The Hudson Institute of Indianapolis reviewed 20 years of research on CBT (computer based training) and found an average 40% time reduction in learning.There is also the savings associated with eliminating travel and accommodation costs, delivery costs, use of internal facilities, and costs of internal trainers and administrators.

Now, this is not always the case, online training could end up being more expensive if the program needs to be developed and designed. If this cost is high, then you will need a guaranteed larger audience to help ensure cost effectiveness. However, if the product is already developed then you will only have to pay for delivery to your population and can avoid the development costs.

Online training has also been shown to improve learning and comprehension. However, it is crucial to understand that this method of training is not applicable for all topics. It would not be effective for training psychomotor skills, such as riding a bike, and it might not be the most appropriate medium for certain topics, such as face to face selling skills or management techniques.

In studies of six major companies, the Interactive Multimedia Association identified that training comprehension was 38-70% faster. Another study by this association showed learning gains 56% greater and content retention 25-50% higher with online training.One of the largest benefits of Online training is accessibility. A study conducted on behalf of the UK Department of Education and Employment by Epic Group plc, in the Spring of 1999, showed that the number one driver for introducing online learning was accessibility. The same study showed that within five years, online learning would account for over 20% of all training, while the classroom would drop from over 50% to 30%. On a company level, accessibility is a benefit when you have a large number of people that have to be trained in a short period of time, when you have a number of locations spread over a large geographical area, and when you want to roll out a company wide training program efficiently and effectively.

Based on trends and research it seems as though Online training is here to stay and as long as we filter the topics we cover, ensure the medium is the most optimal and validate the usability of the program we will all profit from the cost effectiveness of it.

References

Clive Shepherd, Perspectives on cost & effectiveness in online training.

URL: http://www.fastrak-consulting.co.uk/tactix/Features/perspectives/perspectives.htm

To Top

Ergonomics: Cost Savings extends further than injury cost reductions

Many articles have been written on how the application of Ergonomics in industry can lead to a reduction in injuries and a resulting decrease in the associated injury costs. The implementation of an ergonomics program can have a large influence on the number of Cumulative Trauma Disorders, in some cases demonstrating an 80% reduction (Macleod, 1996). The actual costs of implementing such a program is thought to be hefty although case studies have shown that after a five year period an overall cost savings of up to 40% can be realized (MacLeod, 1996). Additionally, because ergonomic interventions are usually a long-term investment, the savings reaped from the implementation of those recommendations can be felt for years, with the total cost savings increasing with each additional year.

As the added benefits of ergonomics on productivity, morale and quality improvements have not been openly discussed, the full value of ergonomics as a cost savings tool has not been realized. This will be an important benefit, especially during the current economy, as industries are continuing to look for new money saving techniques. As we know, injuries occur when the work area is disorganized, when workflow is awkward, and when employees are unaware of potential hazards. Although these scenarios lead to injury, the underlying problems with productivity, quality and reliability are often the root causes. As such, it makes sense to report cost savings with respect to those causes.

When an injury occurs at work there are direct as well as indirect costs that are associated with that injury. The direct costs are related to the observable cost of the injury, the sum of the Estimated Actual Claim Costs (from your latest neer statement) for all claims. These include WSIB compensation payments, continuation of benefits, First aid application, External medical costs, Emergency treatment, Follow up treatment, Clinical or treatment fees (doctor, physiotherapy) and WSIB premium increases.

Average lost time WSIB claim direct injury costs have been estimated at $11,771 (WSIB, 2001). However, the total estimated average cost of a workplace injury is $59,000. This average includes all of the indirect costs that are several times the amount of the original WSIB claim.

The indirect costs refer to the injured workers loss of production, supervisor loss of production (time spent dealing with accident detail consequences), co - workers impacted by accident - loss of production, overtime wages for loss production, cost of the hours spent conducting the accident investigation, cost of hiring new replacement workers, cost of training the worker and paying the trainers.

Indirect costs are often difficult to quantify due to the sometimes far-reaching impact of an injury on a workplace. The WSIB has determined that the approximate total indirect injury costs are equal to the sum of the total non-pension and pension costs for all claims (Estimated Actual Claim Costs) X 4.

Further, not included in the above stated costs, are many hidden indirect operational costs that are often overlooked. These include the cost of cleaning up the accident, repairing or replacing damaged equipment and tools and costs associated with failure to meet production deadlines.

Ergonomic consultants advocating the benefits of ergonomic programs often get caught up in justifying the initial costs in terms of "possible" injury reduction. However, this is not always seen in a good light, as there are no guarantees. High-level managers prefer to see cost savings in tangible components. This is where quantification in terms of real productivity and quality improvement can prove beneficial.

Placing the costs of an injury in terms of the equivalent profit required to counter the same money lost as a result of the injury could grab management's attention.

For example, if your profit margin is 6%, it requires almost $1,000,000 in sales to produce the $59,000 in profit to counter the cost of one lost time injury. Or reversing that, a reduction of one injury has the equivalent profit effect as increasing sales by almost a million dollars at a 6% profit margin. (Courtesy, WSIB, 2001)

The production costs can be displayed as time gained, wages saved, decreased errors, decreased scrap, and less overtime required to make the same amount of product.

Related to both injury reduction savings and business savings is an overall increased morale, fewer physical job complaints, and improved relations, which results in a decrease in employee turnover. Not only are you saving the costs of training new employees but also the administrative costs of hiring new employees, which has been estimated at 50% of annual salary (Shulenberger).

The biggest challenge when looking at the cost justification of ergonomic programs and improvements is quantifying both the costs and benefits. This can be both difficult and time consuming. There are few resources available to help determine the cost benefits of introducing an new piece of equipment, making changes to existing equipment, training employees or implementing a full ergonomic program.

An excellent resource for aiding in making a business case for not only ergonomic improvements but also general health and safety improvements is the WSIB publication, Business Results Through Health and Safety, 2001. We have used this document, along with general business principals to put together a cost benefit analysis tool that allows you to input your own numbers to come up with a specific and reliable cost benefit analysis

We are currently in the process of making this cost benefit analysis tool available on our website free of charge. For more details, look in the "Tools" section on our website.

References

Alexander, David C., "The Economics of Ergonomics",

URL: http://www.ergoweb.com/resources/reference/manergo/alexand.cfmChong, I, "The Economics of Ergonomics" 1997-2001,

URL: http://www.aopd.com/econo.htmlEmployer Tool Kit, Implementing work/life programs, URL: http://www.mdchildcare.org/mdcfc/for_parents/pdfs/CostAnalysis.pdf

MacLeod, Dan., The Ergonomics Edge. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. 1995.

MacLeod, D. and Morris, A., Ergonomics Cost Benefits Case Study in a Paper Manufacturing Company, Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 1996.

Shulenberger Chris C., "Cost Benefit Analysis of Ergonomics",

URL: http://www.claytongrp.com/ergo_costanal_art.htmWSIB publication Form 5031A (10/01)., "Building results through Health and Safety", URL: http://www.wsib.on.ca/wsib/wsibsite.nsf/public/BusinessResultsHealthSafety.html

To Top

Useful Links

Upcoming Events Canadian HR Reporter, Calendar of Events, www.hrreporter.com IAPA's "Growing Our Future" Health and Safety 2002 Conference

URL: http://www3.sympatico.ca/matkins/conf2002/16th International Annual Occupational Ergonomics and Safety Conference

URL: http://zeus.uwindsor.ca/isoes/Helpful References WSIB Cost Benefit Analysis Document, "Building results through Health and Safety", URL: http://www.wsib.on.ca/wsib/wsibsite.nsf/public/BusinessResultsHealthSafety Elements of Ergonomics Programs, Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSD's) & Workplace Factors NIOSH, 1997. URL: www.cdc.gov/niosh/ergosci1.html Canadian Occupational Health and Safety Statistics

URL: http://info.load-otea.hrdc-drhc.gc.ca

To Top

Case Study: Automotive Seat Assembly Company.

Introduction

Ergonomics within manufacturing industry, especially the automotive sector, has been widely accepted for a number of years. As a result, ergonomics has become an integral factor in Manufacturing Health and Safety, Human Resources and Engineering programs. Although this is accepted, we rarely are able to capture the true effects of implementing ergonomics on a wide scale, long-term basis. Fortunately, we have been able to capture the effects of implementing ergonomics at an automotive seat assembly plant over a 5-year period. The following case study outlines the type of ergonomics support provided as well as the results that this support helped achieve.

Method of Integrating Ergonomics into Plant Operations

Prior to 1998, this company had utilized a number of ergonomic consulting firms for sporadic issues. In 1998 they decided to implement a plant wide ergonomics initiative.

Physical Demand Analysis (PDA's) and Risk Assessments

The first stage of this included completing Physical Demands Analysis (PDA's) and Risk Assessments on all of the jobs.

On an ongoing basis, Physical Demand Analysis (PDA's) and Risk Assessments were completed following any job change to ensure that no new concerns were created. If concerns were identified, they were contained and then addressed through engineering controls if possible. This process provided the Union and management with reference reports and material on each job to refer to if issues or concerns were raised. Having access to these reports facilitated the resolving of recurring issues.

Having updated PDA's and Risk assessments was also a crucial part of the job matching and return to work process.

Ergonomic Assessments

Detailed assessments of specific concerns were completed on an as needed basis. These reports were utilized to address concerns/ work disputes and refusals as well as to aid in the design or re-design of tools, workstations and assembly processes.

In 1999, the assembly process was changed from cellular to linear. Through this transition we worked with the engineering design team to determine the ideal set-up of each workstation. This included analyzing the tasks that would be completed at each station in order to obtain the ideal working heights and locations of items. By participating in this process we were able to assist in designing out areas of concern that were present in the original design while ensuring new concerns were not created.

Job Rotation

Job rotation was implemented in order to minimize worker exposure to risks as well as to improve worker satisfaction. This was difficult to implement but has become more accepted over the last 5 years.

Increased Internal Resources On-site physiotherapy and a part time occupational health nurse were introduced to the plant in 1999. These services improved workers treatment options as well as management of injured workers. These professionals complimented the ergonomics initiative as they utilized physical demands analysis and risk assessments to assist in return to work and modified duty scenarios.

Statistics

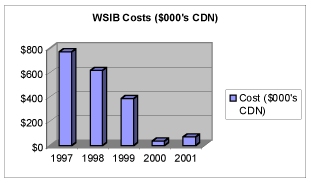

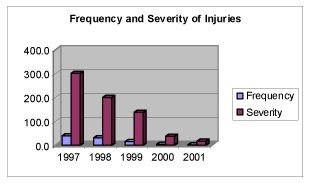

The following demonstrates the injury related statistical history of this company over a 5-year period. Although ergonomics cannot claim full praise for the decreases seen here, it has been acknowledged as one of the main contributors.

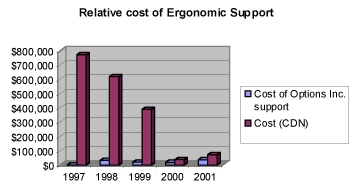

Costs of Ergonomic Support

In attempt to understand the costs associated with the type of ergonomic support outlined in this case study we have plotted the actual ergonomic support costs against the WSIB costs per year. This demonstrates clearly that the cost of implementing the ergonomic initiative was both economical and feasible.

An important point that should be noted is that this ergonomic support has been provided over the last 5 year period with nothing more formal than an "Open" Purchase Order to facilitate the billing process. This demonstrates that in order to implement an ergonomics program you do not need to hire a full time Ergonomist. Your program can be very effective and efficient by developing a relationship with an ergonomic consultant who is able to provide the support you require on an as needed basis.

To Top

Heat Stress

With summer quickly approaching and the warm weather upon us soon, (hopefully), we look forward to spending more time outside enjoying that weather. However, the heat of summer can wreck havoc on many workplaces. Heat Stress is a very big concern in most non-climate controlled workplaces. Heat Stress refers to our body's ability to handle an increase in internal body temperature and maintain homeostasis. Heat stress is related to the environmental temperature and humidity, the age of the worker, the workers physical working level, acclimatization and medical conditions. Heat Stress becomes a problem when our body's internal temperature rises and we are not able to lower it via evaporation of sweat, for example. An internal body temperature of 38°C leads to heat exhaustion and as the temperature increases it can lead to heat stroke and possibly death. Of particular concern are those workers that work near ovens and other sources of heat. Last year, a man died from heat stroke, working in a bakery during one of our summer heat waves. It is estimated that approximately 200 workers in the U.S. and 20 in Canada die annually from occupational heat stress. Actual numbers of related fatalities are likely higher, as many heat-related deaths are attributed to other causes such as heart attack. http://www.whsc.on.ca/HeatStress.html

What can you do to reduce the heat stress in your workplace?

One method from the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) requires a determination of the physical level of work and the measurement of WBGT (Wet Bulb Globe Temperature). Based on these factors, recommendations for Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) for working in hot environments have been made that indicate the amount of rest or breaks that are required. If you are interested in obtaining more information on this process you can refer to the following publication.

- 2001 TLVs and BEIs - Threshold Limit Values for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents and Biological Exposure Indices. Cincinnati: American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH), 2001

- Or check out the information from CCOHS at: http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/phys_agents/hot_cold.html

- The Ontario Ministry of Labour also provides detailed information regarding the control of heat stress at: http://www.gov.on.ca/lab/ohs/heate.htm

Some General Reminders when working in heat or outdoors:

- Mechanize labour intensive processes

- Work slower

- Work in a shaded area

- Use hats and light weight, long sleeved shirts, light coloured clothing

- Ensure clothing does not restrict air circulation at the neck, waist, wrists or ankles

- Isolate the heat source using shielding

- If able to, wear as little clothing as possible

- Do not wipe sweat away as it allows for cooling via convection (air flow)

- Remember whether at work or home to stay hydrated and wear sunscreen or protective clothing when working outdoors

If you are interested in obtaining more information on workplace specific heat stress programs please contact us at 1-800-813-4202.

To Top

OSHA Introduces a Plan for Voluntary Guidelines to Reduce Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSD's)

On April 5, 2002, OSHA, the US. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration, submitted a news release making a commitment to develop a comprehensive approach to ergonomics that they believe will quickly and effectively address MSD's in the workplace. The voluntary ergonomic guideline is based on preventing injuries, using sound science, and providing incentives for employers. The approach is created to provide feasible program outlines for employers both large and small. There are four areas of concentration in the approach including guidelines, enforcement, outreach and assistance and research.

The plan stated that OSHA hopes to develop and release ergonomic guidelines that are task or industry specific with the goal of producing effective and feasible solutions starting within the next six months. Additionally, OSHA will encourage other industries to create their own industry specific guidelines.

The plan states that OSHA will rely on the OSHA General Duty Clause, Section 5(a)(1) to enforce ergonomic application with the goal of reducing workplace injuries. The plan is laid out as a voluntary guideline that recommends a course of action. It is not as rigid as the previous Ergonomic Rule and does not outline specific duties for the employer or employees. Employers cannot be found in direct violation of it, as these will be guidelines, not a standard or a rule. Instead, failure to implement it could result in employers workplaces being inspected, cited and given an ergonomic hazard alert letter with recommendations made under the General Duty Clause. The OSHA Ergonomic Coordinator will then be required to follow up, within 12 months, on the issues.

OSHA will designate 10 Regional Ergonomic Coordinators to conduct inspections for ergo hazards, cite employers and issue ergonomic hazard alerts where deemed necessary. OSHA has stated that they will not be targeting employers that already have ergonomic programs in place and are acting in good faith to reduce MSD's.

The new Ergonomic Coordinators will also provide outreach and assistance via the development of ergonomic training materials, training employers and employees on the risks and prevention of MSD's, and developing a list of compliance assistance tools. The plan is to also develop new recognition programs to highlight the achievements of worksites with novel or exemplary approaches to ergonomics.

OSHA has stated that it will charter an advisory committee to identify gaps in ergonomic research and encourage researchers to design studies in areas where additional info is required.

US industry and labour have mixed reviews for the Plan. USA Today reported that business leaders who had opposed any regulations voiced cautious praise of the announcement, while labour leaders are berating the strategy as ineffective. Statements made by the US Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturer's have both praised OSHA for encouraging additional research in ergonomics however, both continue to be concerned with the enforcement of the guidelines. Some fear overzealous enforcement while others such as the AFL and NYCOSH fear the lack of a formal regulation will limit enforceability and the ultimate goal of reducing employee exposure to ergonomic risks.

What does this mean to us in Ontario?

In ergonomics we are often looking for best practices to implement in our workplaces. Workplaces, employers, and the field of ergonomics, will benefit from the guidelines that are to be developed and the increase in research that should result.

Ontario does not have ergonomic legislation currently in place although many organizations are pushing for it. The Ontario Ministry of Labour (MOL), using the General Duty Clause (Section 25) of the Occupation Health and Safety Act, is currently enforcing and encouraging the application of ergonomics in the workplace. This is similar to what is being proposed in the US with the exception that workers in Ontario have the additional right to refuse to unsafe work (including jobs with ergonomic risks). As well, in Ontario the MOL has the ability to cite, make orders and apply fines under the act. Advocates for ergonomic legislation in Ontario that were hoping the US would lead the way will be disappointed.

We will continue to keep you updated through our newsletters. We will also post information and links to the task and industry specific guidelines as the information becomes available.

For more info please see the following links.

www.osha.gov/ergonomics

To Top

Working and Lifting Safely During Pregnancy

General Information

What happens to the back during pregnancy?

As the pregnancy progresses there are changes to the body that include an increase in body mass, stretching and weakening of the abdominal muscles, and a change to the body's center of gravity. The body adapts to these changes with an exaggeration of the curve in the lumbar spine (lower back). This can make some tasks more difficult especially when standing or carrying loads. This can include tasks that require reaching forward or above the shoulders to access a load, or even sitting in one position for a long period of time.

Are pregnant women at higher risk for back injury? Why?

Yes, pregnant women are placed at higher risk for back injuries. Poor posture can contribute to the backache experienced by many pregnant women. The added weight and its location decrease the ability of pregnant women to keep the load close the body. The change centre of gravity places the woman off balance.

As well, the increased stretch in the ligaments may make the back (and other joints) more vulnerable to injury when lifting heavy weights (or participating in some sporting activities).

Other changes that may effect work ability.

In addition to the changes to the spinal alignment there are changes to:

- Circulation: There are increases in blood volume and the amount of blood pumped by the heart (cardiac output). This reduces the heart's ability to adapt to exertion and also increases pressure in the veins in the legs, which makes standing for long periods difficult and uncomfortable.

- Body weight: Women gain weight during pregnancy, some more than others, most noticeably during the last 6 months. Some of this weight gain is due to an increase in body fluids and fat deposits, and the rest is from the growing foetus.

- Ligaments: Changes in hormone levels in the body cause ligaments to become more easily stretched, especially later in pregnancy.

Environmental and physical changes include:

- Pregnant women often find that they cannot tolerate hot weather very well, especially in the later stages of pregnancy, and this may be a problem if a woman is also working hard.

- The excess weight that she is carrying has to be added on to an employee's usual work load and may increase feelings of fatigue.

Work Specific Information

What tasks are risky for pregnant women?

Some tasks are associated with a higher risk level when completed by a pregnant worker. Some of the potential risk factors related to manual handling activities during pregnancy are:

- Fatigue due to physiological changes in conjunction with an excessively long work week;

- Prolonged standing (for more than 3 hours per day);

- Heavy physical workload (continuous or periodical physical effort, carrying loads of more than 10 kg);

- Working under hot working conditions if a lot of sweat is being produced;

- Frequent forward bending, stooping or reaching above shoulder height, even when light loads are being handled.

What can you do to reduce the risk?

Practice and use correct posture and proper lifting techniques. The following are tips to remember when working in general and when lifting.

General Working Posture

- Straighten your upper back so your ear, shoulder, and hip are all in alignment.

- Tuck your pelvis to maintain a pelvic tilt at all times.

- Contract your abdominal muscles.

- Avoid standing in one position for a long period of time.

- Avoid high heels.

- Use a step stool to rest one foot on if you have to stand for a prolonged period of time. This decreases the sway in your lower back.

- When getting in and out of bed or a car, turn your hips, pelvis and back in the same direction while maintaining a straight back. When getting out of bed, first roll to your side and then use your arms to push from the bed

Lifting Posture

- To reach or lift low objects, spread your feet apart with one foot ahead of the other and bend your knees

- If you have to pick something up, kneel down on one knee with the other foot flat on the floor, as near as possible to the item you are lifting.

- Lift with your legs, not your back, keeping the object close to your body at all times. Be careful, though - it may be easier to lose your balance while you are pregnant.

- When moving an object, push it instead of pulling it. Use your legs, not your back and arms.

- Never bend at the waist with your knees straight, even if it is only a slight bend. Instead, alter your position so that you are sitting, squatting, kneeling or bending at the knees while leaning forward at the hips.

- Whenever possible, get assistance in lifting objects.

Carrying

- · Two small objects (one in either hand) may be easier to handle than one large one. If you must carry one large object, keep it close to your body.

General Recommendations

- Take breaks. Put up your feet if you've been standing, or stand and walk around every two hours if you've been sitting. This will help decrease swelling in your feet and ankles and it should keep you more comfortable. Throw in a few stretching exercises to protect your back.

- Rest when you can. The more strenuous your job, the more you should reduce physical activity outside of work.

- Take time to eat regular meals. Choose lunches that are balanced and nutritious

As an employer what can you do?

Some practicable control measures that can be implemented include:

- Reviewing the work tasks undertaken to avoid heavy work duties. In particular, avoidance of extremely heavy physical exertion in early pregnancy and a reduction of the physical workload after the third month and again after the sixth month of pregnancy;

- Reducing, if possible, the amount of time spent working under hot conditions, or improving workplace climate or ventilation, especially if heavy work is involved;

- Reviewing work tasks that require a lot of bending and reaching, especially late in pregnancy, in order to reduce as much as possible the range of movements required;

- Provision of rest breaks during the day.

References

http://www.safetyline.wa.gov.au/pagebin/pg000133.htm

http://babies.sutterhealth.org/during/preg_posture.html

http://www.babycenter.com

To Top

The Role of Ergonomics in the Return to Work Process

Increasing medical, rehabilitation, WSIB and insurance costs have caused many companies to re-examine their current process and policies for Disability Management and Return to Work. These new programs are set up to decrease frequency and length of time away from work, as well as, to ensure the employee's safe and effective return to work. In attempt to facilitate these objectives, many of the programs now include the addition of ergonomics.

Ergonomics has many facets that are useful in the Return to Work process. For example, this could include determination of essential physical demands of the job, (re) design of the workstation, or modification of the job/equipment.

This process is most effective when completed with a multi-disciplinary approach. When this approach is utilized within a company, the Company Doctor, Occupational Rehab Nurse, Ergonomist, Placement person and the Union rep (if applicable) all have roles. In some plants there may not be a different person for each role but the responsibilities are typically covered.

The Role of the Ergonomist

The Ergonomist interacts with all persons involved in the return to work process. They provide pertinent information with regards to the job and an objective view of the employees' ability to complete the job.

Ideally, the Ergonomists role will involve:

Completion of physical demands analysis - A physical demands analysis or PDA is a detailed assessment of the physical and cognitive requirements of the job. PDA's are most effective when they break the job down into tasks, outlining the essential duties of the job and the physical movements required to complete them. Ideally, PDA's should be completed on all jobs to allow for job matching to be completed plant wide. Then, if a worker cannot return to their pre-injury job, a search of jobs plant wide could be completed.

Job matching with the employees restrictions - All employees returning to work should arrive with a doctor's note, or form, outlining that they are fit to return to work and any specific physical restrictions. These restrictions should identify the postures and forces that should be avoided. A restriction stating that a worker cannot work on Machine #11 is not suitable and should not be accepted. Use of the WSIB Functional Abilities Form is a common practice with many doctors and workplaces. However, occasionally this form may need to be interpreted or enhanced to capture the employees' true abilities. The Company Doctor and/or Occupation Rehab Nurse can usually provide an accurate interpretation. Once the workers true ability or restrictions have been determined then direct matching with the jobs can take place. Ergonomists have the background to conduct this analysis and make these decisions objectively. Once a decision has been made to return the worker to the pre-injury, or another, job within the workplace a Return to Work Plan can be formulated.

The Return to Work Plan - This plan is usually developed with the Ergonomist, Occupational Rehab Nurse, placement person and the Doctor. If a gradual return to work is required, modifying the duties or the hours may be required. If this is needed, coordination with the Supervisors and Management is mandatory. Ideally, once a plan has been formulated, all those involved meet to review it and discuss any concerns. This meeting should include the employee, the Occupational Rehab Nurse or Placement person, the union rep, the supervisor and the Ergonomist. Any problems can then be addressed before the plan is implemented. It should be noted that employees on modified duties may require additional help with certain tasks or should be placed as an extra person on a job. They should not work overtime hours during their return to full duties.

Making Accommodation Recommendations - When the workers restrictions don't match any of the available jobs within the workplace, the Ergonomist's expertise should be used to determine if any of the available jobs could be modified to allow the worker to return to it. Changes can be very simple or complex and often require interaction with the engineering department to determine if it can be completed.

Education and Training - The ergonomist can be available on site to help the worker return to the job through job coaching. Job coaching involves working with the employee to provide alternate posture recommendations on how to complete the job within their restrictions. It may also involve educating the worker on how to adjust the workstation, take breaks as needed and complete specific stretches and exercises to aid in the successful return to work. Also, this time will allow the ergonomist to discuss any specific concerns that may arise. If a worker cannot complete the job, a change to their restrictions to more accurately reflect their abilities may be required. Or if it is deemed that there is no reason why the employee cannot complete the job this should be documented.

Working with the Family Doctor and Specialist - It would be ideal if all Doctors could visit the workplace to give them a better idea of what each job requires. Of course, this is not possible and therefore, it is highly recommended that the Family Doctor be provided with the physical demands of the job. Additionally, once a return to work plan is arranged it should be sent to the employee's Doctor for a final sign off. If a job match has been completed and outlined in the return to work plan the Doctor can make his/her decision on the objective information provided. Many Doctors prefer this approach.

Whoever you have available at your workplace in these roles, an ergonomists can help provide objective information on the job and the job matching to get employees back to work sooner, safer and more effectively.

In addition to providing services as an Ergonomist in the Return to Work process of many companies, Options Inc. has created a program that completes objective job matching. The program requires the input of essential physical demands of the job and compares it to the restrictions provided by the Physician. It utilizes the WSIB Functional Abilities Form and provides an area for worker and management to sign, agreeing to the return to work and space for a return to work plan should one be created. The Options Inc. Job Matching Program allows job matching to take place on off shifts when return to work personnel may not be available. Please contact us if you wish additional information on this tool or a preview of it.

To Top

What is CCPE?

Our clients and regular visitors to our website may have noticed that we now have four letters, CCPE, that follow our names. These letters stand for Canadian Certified Professional Ergonomist. They provide a means of designating and recognizing professionals that have been accepted by the Canadian College for Certified Professional Ergonomists. In order to achieve this recognition you must demonstrate that you have met specific criteria in terms of education and professional experience. The Board of the College is made up of eight certified ergonomists that work in academia, government, industry and consulting fields.

Why do we need CCPE designation?

Certification is important both for ergonomists and for the users of ergonomic services. It is beneficial to:

- Protect users of ergonomics services,

- Protect the reputation of ergonomics, and

- Improve quality of practice.

What does this mean?

By having our CCPE it demonstrates that we have met the criteria in terms of education and professional experience to ensure we have:

- The knowledge and skills necessary to work in the discipline,

- Adequate familiarity and competence with the tools and methods used to apply their knowledge and skills in the field, and

- Experience with the application of the tools and feedback on their use.

To our current and future clients, it means that we will continue to provide you with accurate, detailed analysis and designs that stem from the most up to date research available. It gives you the added comfort of knowing we have attained and continue to attain a high level of quality and professionalism in the work we undertake.

For more information on CCPE see the following website: www.ace-ergocanada.ca

To Top

Make your "two cents" count!

User input is often requested in attempt to improve the performance or design of a product. Evaluating the usability of products is a stream of ergonomics and human factors that can have a direct impact on you as a product user. It also allows you an opportunity to provide feedback to the manufacturer or designer of the product.

User trials can be completed through focus groups, questionnaires or simulations and trials. With the increased use of the Internet it has become easier to get a large audience to participate in user trials. Although a large number of users can be reached in an economical manner, the validity of the information could be questioned due to the nature of the uncontrolled environment.

This link (http://www.openerg.com/nurserygoods/index.htm) connects you to an on-line User Questionnaire for Nursery Products, being conducted by a company from the UK. If you have experience with any of the products in question, feel free to complete the questionnaire and include your feedback.

Note: This trial is not related to Options Inc. in any way. The link is being included in attempt to demonstrate the depth of the field of ergonomics to the general population.

To Top

Summary of NIOSH Back Belt Studies

March 2002

This article is from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/beltsumm.html

In two 1994 NIOSH publications, Workplace Use of Back Belts - Review and Recommendations (94-122) and Back Belts - Do They Prevent Injury (Pub. No. 94-127), NIOSH concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend the use of back belts as a back injury prevention measure. Since then, NIOSH conducted a large epidemiologic study and two laboratory evaluations to determine more conclusively the effects of back belt use. They do not provide evidence to change NIOSH's earlier conclusions.

To examine the effects of back belt use on back injuries in the workplace, a large, prospective cohort study was conducted among material handlers in a retail setting. Controlling for multiple individual risk factors, this study found that elastic support back belt use was not associated with reduced incidence of back injury claims or low back pain (Wassell, et al., Journal of the American Medical Association, 284 (21), December 6, 2000).

Two laboratory evaluations examined the physiological and human motion effects of the same belt as used in the prospective cohort study. A laboratory evaluation of the physiological effects of belt use found a significant reduction in mean oxygen consumption, but no significant effect on heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate (Bobick, et al., Applied Ergonomics, 32(6), 2001). An evaluation of the effects of the elastic back belt on human body motion during box-lifting tasks found that use of the belt significantly reduced the distance of forward spine bending and the velocities of forward-and-backward-spine-bending among subjects in the laboratory setting (Giorcelli, et al., Spine, 26(16), August 15, 2001). Unlike the epidemiologic study, these laboratory evaluations did not examine the association between back belt use and the outcomes of back injury or back pain.

In summary, recently completed research found that belt use reduced spine bending in laboratory trials. However, elastic support back belt use among retail material-handlers was not associated with reduced back injuries or back pain.

To Top

Children and Computers - do they fit together?

By now, many adults have heard of Repetitive Strain Injuries and understand the need to set up their computer properly. They may also understand how ergonomics assists them in achieving optimal postures when working at computer workstations. However, how many of these people pass on their knowledge to their children and/or students? Unfortunately not enough.

Our children are increasingly becoming at risk of developing RSI's at very early ages. One study, from the University of Rochester, found that when sixth- through eighth-graders were asked whether they experienced computer-related aches or pains at home or school, a total of 47 percent experienced discomfort with wrists; 44 percent with neck; 43 percent with eyes and 41 percent with hands.

Why are children at risk?

- There is an increase use of computers at home and at school. It is possible, that an active young child can strain his back or neck after spending an hour or so on the computer with poor posture habits. Eyestrain can also be a concern if the monitor is not positioned properly and periodic eye breaks aren't adhered to.

- Few schools and fewer homes have their computer workstations set up for children. As a result, children are working at computer stations designed for adults. Ergonomic and environmental psychology researchers found that almost 40 percent of the third-to-fifth graders studied used computer workstations that put them at postural risk; the other 60 percent scored in a range indicating "some concern." None of the 95 students studied scored within acceptable levels for their postural comfort. The typical office chair isn't designed for users under 5 feet tall. As a result, your child doesn't fill the seat out the way an adult would. Most experts agree that children can sit for about an hour in adult-sized chairs without any discomfort. For longer periods of sitting, it's recommended that you adjust or modify the chair better fit your child.

- Their small body size and developing bone and musculature.

What can be done?

- Investigate purchasing equipment made for children. Children have special needs when it comes to computers and accessories. These include a smaller mouse for smaller hands and footrests that support the dangling feet of children in adult-sized chairs. Some suppliers are now making computer desks, chairs and equipment for children. Some examples are: Little fingers (kid sized keyboard, http://www.datadesktech.com/), Kidzmouse (kid sized mouse device, http://www.kidzmouse.com/), computer desks and chairs, (http://shop.store.yahoo.com/trains-4-tots/kidcomdescha.html)

- Alter current equipment to make it suitable for children. For example, add a back cushion to an adult size chair, provide a height and angle adjustable footrest, provide an adjustable tilt down tray for the mouse and keyboard.

- Set up the workstation for optimal postures:

- The child should be positioned comfortably with their feet solidly on the ground or on a footrest.

- The legs and hips should be perpendicular to the spine (at an angle of between 90 and 100 degrees).

- The spine should be straight and the small of the back should be supported.

- Wrists should be in a neutral position when typing and using the mouse, not overly flexed or extended.

- The elbows should be bent at a 90-degree angle to the upper arm and close to the side of the body.

- The top of the monitor should roughly align with the child's forehead, allowing the head to stay in a neutral position when using it.

- The monitor should be directly in front of the child, not at an angle.

- The monitor should be located approximately two feet away from the child.

- Educate your child on RSI signs and symptoms. Be alert for signs that your child is experiencing discomfort. This may include complaints of headaches, massaging of the neck, forearms and wrists or changing hands for completion of everyday tasks. Medical intervention, a review of their postures, and decreased time at the computer should all be sought if these signs are present.

- Limit the time your child spends at the computer. Encourage your child to take breaks frequently when at the computer (suggested 5 min. break every 20 min. of computer time)

- Exercise and Stretching. Encourage your child to exercise regularly and complete stretching exercises after prolonged periods of computer use. A computer program can be purchased to interrupt computer use and provide stretches to be completed during the break.

Hopefully you can understand the importance of ensuring children use proper body postures and set up when working at the computer. Although their daily time at the computer is less than most office workers, the cumulative time at the computer will be much more than today's office workers. Development and continuation of good habits will hopefully allow them to use computers for years without an incident of an RSI.

* To help you set-up your home computer, work through our Online Tool. This tool will help you set up your station in the ideal manner. The principles covered in this tool can be applied to your children as well as yourself.

References

Workstation Ergonomics Guidelines for Computer use by Children, (as presented on MSNBC Today Show, Jan. 5, 2000), Cornell University Ergonomics Website, http://ergo.human.cornell.edu/cuweguideline.htm

Guidelines for parents interested in reducing the risks of computer related repetitive strain injury in children, Deborah Quilter, http://www.rsihelp.com/children.shtml

Ergonomics for Elementary School Students, Ergonomics Today, Ergoweb, http://ergoweb.com/news/detaile.cfm?id+552

Computers may cause posture problems in children, Computers in Schools, 1998;14:55-63, from website http://eeshop.unl.edu/text/kidrsi.txt

To Top

Is prolonged standing a risk to workers? If so, how can we address it?

Prolonged standing can be a risk to workers. It has been associated with several disorders and can lead to workers suffering from them, as well as, being uncomfortable, less alert and less active. All of these factors can have a negative affect on productivity and the quality of the work being completed.

Workers in jobs that involve static standing postures for more than 4 - 6 hours per shift are at the most risk. These workers include retail, casino, and some industrial workers, supermarket cashiers, and food service staff. Pregnant women are at an especially high risk for varicose veins, increased blood pressure, swelling of the legs and feet, and low back pain when required to work in a standing position for more than 6 hours. In fact, anyone spending several hours standing on a cement or hard surface may be at risk.

Working in a standing posture on a regular basis can cause sore feet, swelling of the legs, varicose veins, general muscular fatigue, low back pain, stiffness in the neck and shoulders, and other health problems (CCOHS).

It should be noted that there is a distinct difference in the types of standing that can occur in the workplace. We categorize these as static or dynamic standing. Static standing is standing in one spot for hours without the opportunity to move around (even within a few feet). Dynamic standing allows the worker the ability to move the feet (i.e. walk) at least every 15 min. or have the ability to walk within a 2-4 ft radius within their regular work/job cycle. Dynamic standing decreases the risk of blood and other fluids from pooling in the feet and allows the muscles of the legs to continue to act as a pump to aid circulation of the blood back to the heart.

Alternating between sitting and standing postures is the ideal working situation. However, providing workers with this postural flexibility may not always be possible. When workers are required to sit for a long period of time the intervertebral disc pressure increases when compared to a prolonged standing posture. This increase can put the worker at an increased risk of a back injury if other risks such as poor posture (long reaches) and high forces (> 4kg when seated) are involved. As a result, each work situation needs to be examined and the appropriate recommendations made.

What can we do to decrease the chance of these health concerns from occurring?

The work area/standing surface

- Design the flooring to be made of a flexible product. Wood, cork, carpeting, and rubber are preferred to concrete or metal grating.

- Use anti-fatigue matting to provide cushioning on concrete and metal grating surfaces. Anti-fatigue matting allows for subtle movements of the leg and calf muscles, which promotes blood flow, decreases foot fatigue and may decrease the occurrence of varicose veins.

The work area

- Allow room for workers to change body positions and design jobs to allow for frequent changes in position.

- Install a foot rail or footrest to allow workers to shift their weight from one leg to the other.

- Design jobs that alternate between sitting and standing (type of work, reach and equipment use must be taken into consideration).

- Rotate workers between jobs that require sitting and standing postures.

Footwear

References

- Wear shoes that do not change the shape of your foot.

- Choose shoes that provide a firm grip on the heel. If the back of the shoe is too wide or too soft, the foot will slip, causing instability and soreness.

- Wear shoes that allow freedom to move your toes. Pain and fatigue will result if shoes are too narrow or too shallow.

- Ensure you have a good fit. Have the shoe supplier measure your foot accurately and fit the shoes appropriately.

- For standing operations, proper support is critical. The primary focus here is on arch support. Good arch support helps maintain the natural curve of the foot while standing and better positions the foot to absorb the shock associated with walking.

- Anti-fatigue insoles are thought to dampen the force of impact during gait but not enough research has been completed to support the use of insoles for their anti-fatigue properties.

Prolonged Standing: taking the load off, Resource Lines, Workers Health and Safety Center, Summer 2002

OSH answers, CCOHS website, http://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/ergonomics/standing/standing_basic.html

White, Heather, Where the Feet Hit the Floor, Occupational Health and Safety Magazine online

To Top

Psychosocial Issues - How do they affect the Risk of Musculoskeletal Injuries?

The presence of certain psychosocial issues in the workplace increases the risk of a person developing a musculoskeletal injury or repetitive strain injury. Some of these stresses are issues such as job stress, job dissatisfaction, and work organizational factors. However, although this is an accepted fact, the physical process of how this occurs is not well understood.

Several theories have been hypothesized in attempt to better understand the connection between psychosocial issues and injuries. For example, it is thought that the presence of a psychosocial issue places a stress load on the body, which can result in biomechanical loading of the muscles, an increase in the release of catacholamines and other hormones as well as a circulatory response. This would exacerbate the influences of the traditional risk factors (Salvendy, 1997). Basically, the way the body responds to the psychosocial stress could be similar to how it would respond to a physical stress.

Additionally, it is proposed that workers under stress will be more likely to use poor working methods and excessive force to accomplish a task. Stress may affect their coping style, motivation to report injuries and motivation to seek treatment. For example, it has been noted that people tend to change their body posture when pressured by deadlines. Further, Theorell and colleagues (1991) demonstrated that increased mental demands are associated with worry, fatigue, and difficulty sleeping which in turn corresponds to behaviour that increases muscle tension and is associated with back, neck and shoulder discomfort (Ergonomics for Therapist, 2000).

Sauter and Swanson (1996) noted that stress-related arousal might increase sensitivity to normal musculoskeletal sensation. This basically means that the worker becomes aware of any small sensation that in other situations would be suppressed. Stress may serve to increase the perception of pain or greater severity of pain and has been related to psychological stress among patients with low back pain by several researchers (Salvendy, 1997).

Recently, researchers from France investigated the physical response of the body to stress and then hypothesized how these reactions could increase the risk for musculoskeletal injury. They found that when the body experiences stress, it may release pro-inflammatory chemicals which can lead to tendon inflammation, the release of corticosteroids which can lead to swelling of the joints and increase the pressure within certain areas of the body. An increase in the pressure within the Carpal Tunnel would increase the risk of the worker developing CTS especially when combined with a job that has poor ergonomics to begin with. From this we can see how being exposed to high stress levels could pre-dispose workers to an increased risk of injury.

Although more research is needed to confirm the direct association of psychosocial stress and risk of injury, the current data suggests that there is some type of strong relationship. As a result, it is recommended that when looking at a job or work area for ergonomic concerns, an examination of the psychosocial issues be included. This could include anything from looking at the job design (piece work, overtime, break scheduling) to an all encompassing assessment of the stress level the workers are experiencing. By including this in the assessment previously missed areas of concern may be identified. This in turn could provide employers additional means of reducing their musculoskeletal injury occurrences other than the traditional redesign of the job.

References

Workplace Stress and Injury - The Latest Thinking, Ergonomics Today, Ergoweb, http://ergoweb.com/

Salvendy, G, 1997, Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, John Wiley & Sons.

Jacobs, K., 2000, Ergonomics for Therapists, Butterworth-Heinemann.

To Top